Excursions Daguerriennes. Vues et Monuments les plus remarquables du Globe.

Author: Lerebours a.o.

Year: 1842

Edition: First edition

Publisher: Lerebours

Volume one only of two (¹), complete with all 60 plates. Contemporary cloth, oblong 4to. (paper size: 245 x 345 mm), unpaginated but collation below. The covers rather soiled and rubbed.

The plates printed on chine collé. The plates overall very clean and occasionally some very light foxing on the mounts, as well as an occasional dampstain. All 60 plates protected with tissue guards.

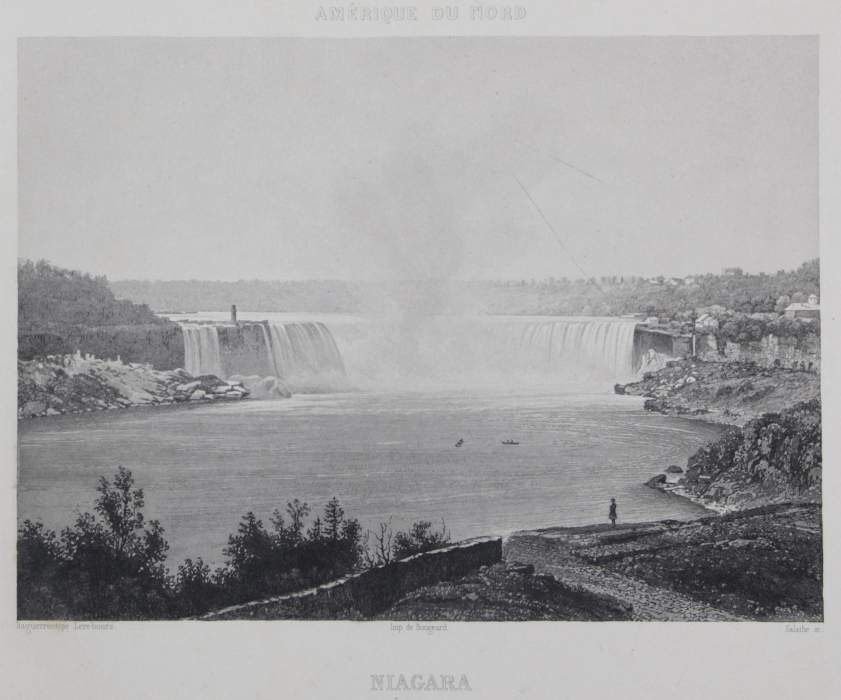

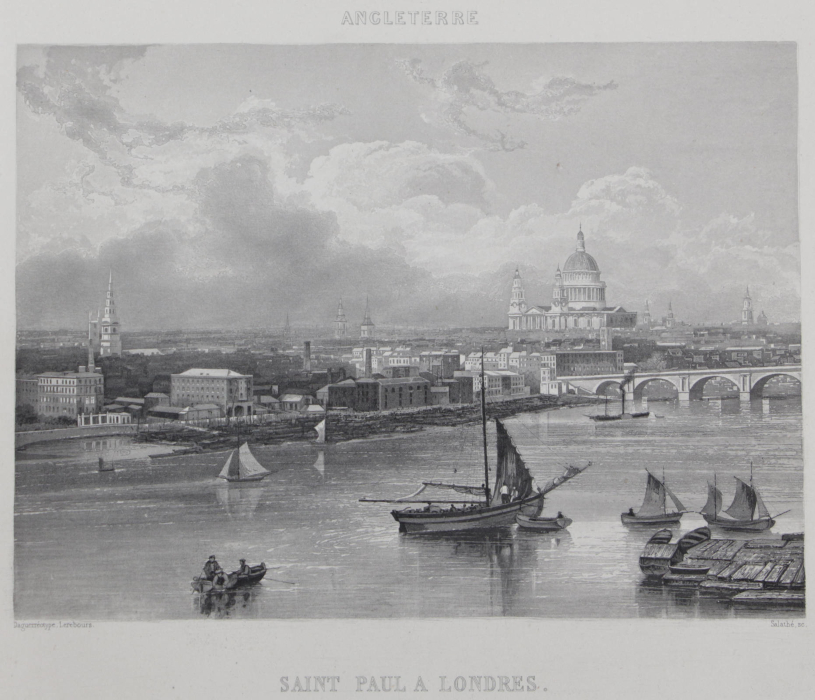

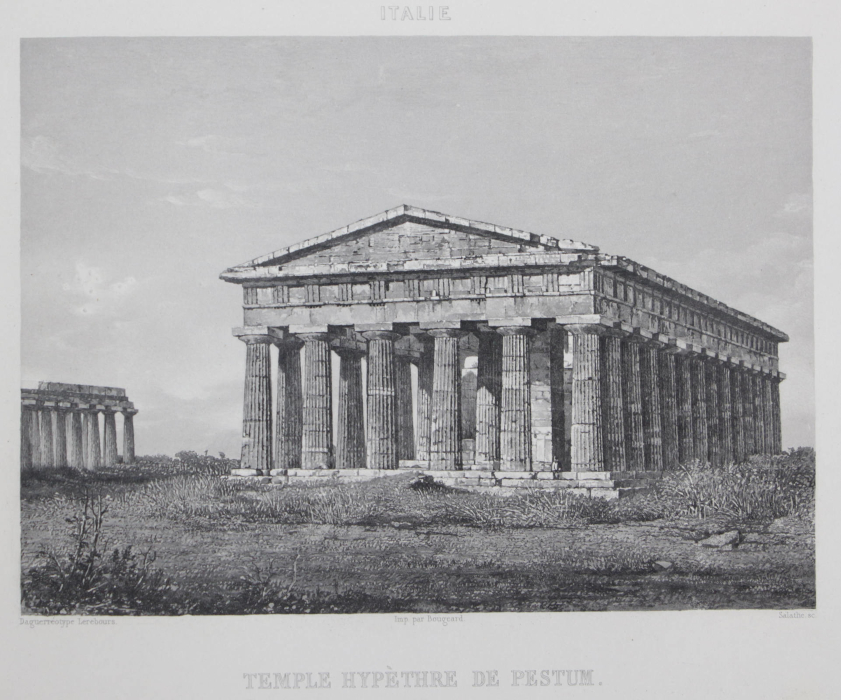

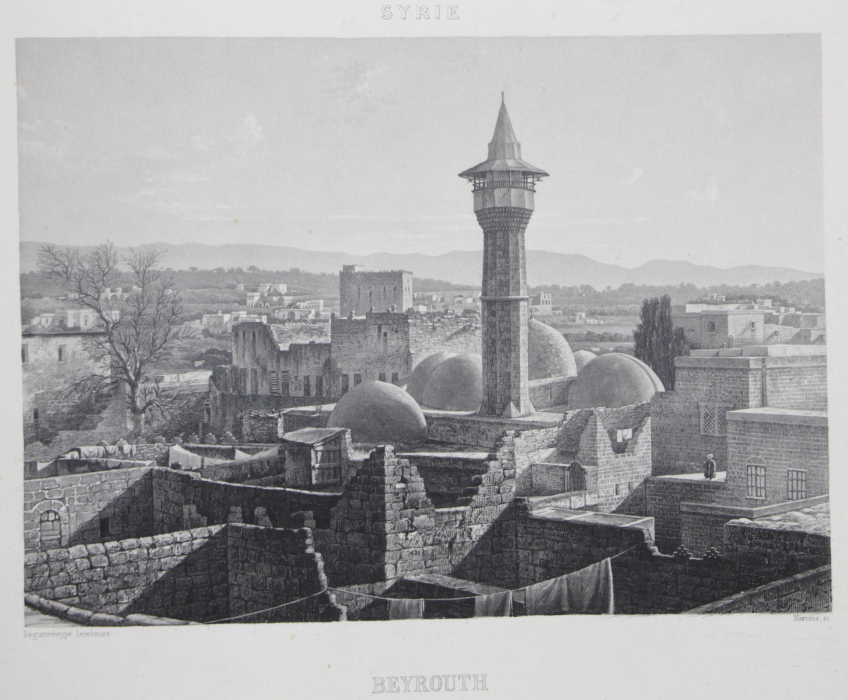

The importance of this book lies in its plates. In 1839 the Daguerreotype was introduced and for the first time in history images could be recorded from reality directly on a metallic plate. This process was far more accurate of course than the drawings made on the spot, the only possible method till then. Lerebours, an optician from Paris, had a keen interest in the daguerreotype process. He was one of the first to understand the immense importance of this process for publishing purposes and took on to publish a book with the worlds known most importants monuments and landscapes at the time, like the ancient temples of Greece and the Niagara Falls. They all can be found in this tome. There was no solution yet (1841-1842) to reproduce the photographs directly to paper, so that Lerebours had these pictures engraved to have them printed.

One of the problems with early photography was the long exposure time required; living objects like people, animals and birds could not be captured. Lerebours solved this by adding figures to the engravings to make them livelier. Although this sometimes nowadays leads to discussions about the accuracy of the plates by some critics, it is generally accepted that these plates were the most accurate to date in the early 1840’s. Details ignored or omitted by many draftsman till then suddenly, sometimes painfully, became visible. As such this is an extremely important book in the history of publishing.

Each plate is accompanied by 2 – 4 pages of letterpress, written by various experts on the subject shown in the respective plate.

Collation with in square brackets the index numbers as per the list of illustrations. In brackets the number of textpages accompanying each plate and in braces the names of the engravers. All plates bound in the correct sequence.

[01] Grande Mosquée à Alger (2); {Callow}

[02] Hôtel de ville de Bréme (2); {Hürlimann}

[03] Niagara (2); {Salathé}

[04] Saint Paul à Londres (2); {Salathé}

[05] Colonne de Pompée (2); {Martens}

[06] Harem de Méhémet-Ali à Alexandrie (2); {Weber}

[07] Louqsor (2); {Martens}

[08] Pyramide de Cheops (4); {Riffaut}

[09] La vallée des Tombeaux (2); {Salathé}

[10] Alcazar de Séville (2); {Riffaut}

[11] Alhambra (2); {Salathé}

[12] Grenade (2); {Salathé}

[13] Les Arènes à Nimes (3 + 1 blank); {Himely}

[14] Maison Carée à Nimes (2); {Callow}

[15] La Tour magne à Nimes (2); {N.P. Lerebours}

[16] Arc-de-Triomphe d’Orange (2); {Hürlimann}

[17] La Colonne de Juillet (2); {Hürlimann}

[18] St. Germain l’Auxerrois à Paris (3 + 1 blank); {Hürlimann}

[19] Porte Laterale de Notre Dame à Paris (2); {Himely}

[20] Vue prise de Pont Neuf à Paris (2); {Martens}

[21] L’Acropolis à Athène (2); {Appert}

[22] Le Parthénon à Athène (2); {Martens}

[23] Les Propylées à Athène (2); {Riffaut}

[24] Maison de Longwood [St. Hélène] (2); {Thiénon}

[25] Place du Grand Duc à Florence (2); {Salathé}

[26] Fort Neuf à Naples (2); {Paul Legrand}

[27] Le Môle à Naples (2); {Salathé}

[28] Temple de Cérès à Pestum (2); {Martens}

[29] Temple Hypèthre de Pestum (2); {Salathé}

[30]Le Duomo et la Tour Penchée à Pise (2); {Callow}

[31] Santa Maria della Spina à Pise (2); {Salathé}

[32] Arc de Constantin à Rome (2); {Himely}

[33] L’Arc de Titus à Rome (2); {Callow}

[34] Les Cascades de Tivoli (2); {Salathé}

[35] Le Colisée à Rome (2); {Himely}

[36] Colonne Trajane à Rome (2); {Hürlimann}

[37] Ste. Marie Majeure à Rome (2); {Price}

[38] Saint Pierre et le Fort Saint-Ange à Rome (2); {Weber}

[39] Place du Peuple à Rome (2); {Martens}

[40] Port Ripetta à Rome (2); {Himely}

[41] Temple de Vesta à Rome (2); {Martens}

[42] Monte-Mario (2); {Salathé}

[43] L’Arsenal à Venise (2); {Martens}

[44] Église Saint Marc à Venise (3 + 1 blank); {Hürlimann}

[45] Pont du Rialto à Venise (2); {Martens}

[46] Vue prise de la Piazetta à Venise (2); {Martens}

[47] Vue prise de l’Entrée du Grand Canal à Venise (2); {Martens}

[48] Vue prise du Clocher de St. Marc à Venise (2); {Salathé}

[49] Temple Hypèthre. Dans l’Ile de Philæ (3 + 1 blank); {Bishop & Weber}

[50] Jerusalem (2); {Salathé}

[51] Moscou (2); {Legrand}

[52] Vassili Blagennoï à Moscou (2); {Legrand}

[53] Vue du Kremlin à Moscou (2); {Hürlimann}

[54] Église de la Marine à Stockholm (2); {Hürlimann}

[55] Genève (4); {Bishop & Weber}

[56] Temple du Soleil à Baalbec (2); {Salathé}

[57] Beyrouth (2); {Martens}

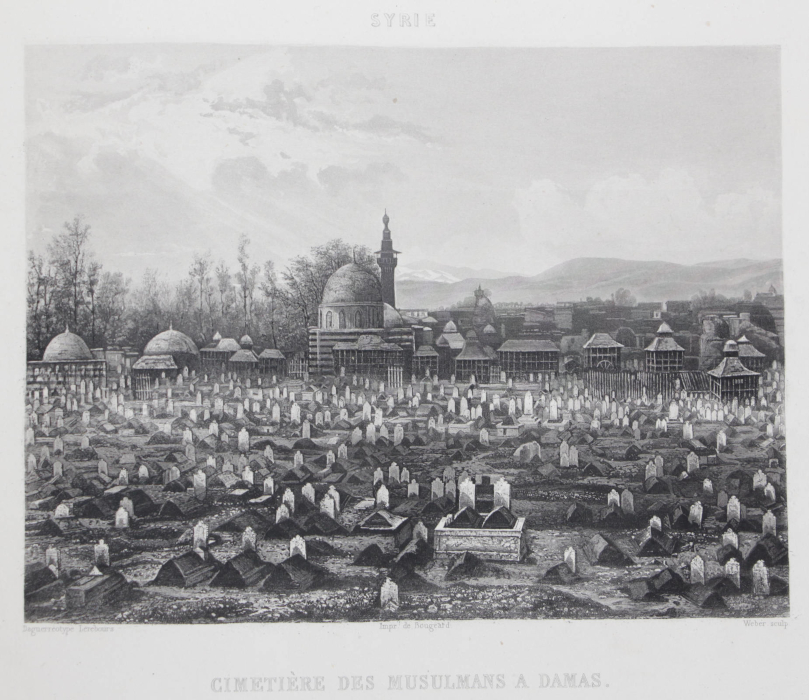

[58] Cimetière des Musulmans à Damas (2); {Weber}

[59] St. Jean d’Acre (2); {Salathé}

[60] Nazareth (2); {Salathé}

Here below the beginning of an article written by Michèle Hannoosh, then professor of French at the University of Michigan, as posted on the website of the British Library August 5th, 2015:

On 19 August 1839, the astronomer François Arago demonstrated to the French Academy the startling new photographic process invented by Louis Daguerre, by which an object was imprinted on a metal plate without human intervention, through the action of light alone. Within just a few weeks, budding daguerreotypists had learned the technique and set off to try their luck in far-flung destinations across Europe, Africa and the Near East.

This was no easy task: the travellers had to transport nearly 300 pounds of equipment, dangerous chemicals and inconvenient supplies; with no precedents to guide them in climates very different from that of Paris they had to experiment with lighting, aspect, exposure times, chemical combinations and conditions for developing the pictures; they often had nothing to show for their efforts but a blank plate. Where they succeeded, however, they produced the first photographic images ever made of these regions, having enormous historical and aesthetic importance, and inaugurated a practice which would forever alter the experience of travel.

But for the foresight of an enterprising Parisian optician and maker of scientific instruments named Noël-Paymal Lerebours, there would be little evidence of this pioneering photographic activity: the daguerreotype process does not allow the plate to be reproduced and few originals survive. Lerebours gathered together over a hundred of these daguerreotypes, had them traced and then engraved: the resulting Excursions daguerriennes: Vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe (Paris, 1841-42; British Library 1899.ccc.18) was the first book to be illustrated from photographs. The images represented sites throughout Europe, from Russia and Sweden to Spain and Greece; around the Mediterranean from Algiers to Beirut; and further afield to the Americas.

Each image was accompanied by a text signed, in most cases, by a professional critic or man of letters. The photographers, on the other hand, are not indicated and most are therefore unknown.

There are two notable exceptions. Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, a Swiss-born Canadian seigneur who was in Paris en route to the Near East when Daguerre’s invention was announced, and Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet, a student of the French painter Horace Vernet whom he was preparing to accompany to Egypt and the Levant, both grasped the potential of the new process and quickly availed themselves of it. Joly left for Greece on 21 September 1839 and became the first person ever to photograph Athens; over the following eight months he took daguerreotypes of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Cyprus, Rhodes, Istanbul, and Malta. Goupil-Fesquet left for Egypt with Vernet in October, taking a slightly different route through the Levant and back to France by way of Izmir and Rome. Both photographers kept journals of their travels and drew upon them for the texts that they wrote to accompany their images in Excursions daguerriennes. Joly contributed the chapters on the Parthenon, the Propylaeia, the temple at Philae, the Temple of the Sun at Baalbek and the Muslim cemetery at Damascus. Goupil-Fesquet produced those on Pompey’s Pillar, the harem of Mehmet Ali in Alexandria, Luxor, the Great Pyramid, Jerusalem, Beirut, Acre and Nazareth.

Our copy of this book, according to the title page, was printed by the firm of Rittner et Goupil. In 1841 Henry Rittner had died and Goupil formed a new partnership with Théodor Vibert. From then on the company was named “Goupil et Vibert”.

The BnF has two copies of this book; one with an identical title page as our copy and another one on which the firm of Goupil et Vibert is mentioned, hence our copy should be an early one.

(¹) Later 54 more plates were printed in a separate volume with a half title only. The majority of those plates deal with France, while the others were taken respectively in Italy, Russia, Sardinia, The Savoy and Switzerland. However, three plates in that volume were printed directly from the plates, thanks to an invention by Hippolyte Fizeau.